Risky Business #6: The impact of natural disasters on county-level delinquency rates

-

Risky Business #6: The impact of natural disasters on county-level delinquency rates

Jan Polách, Oliver Wyman

Introduction

In recent years, physical climate risk has emerged as an increasing concern for financial institutions worldwide. This heightened importance is driven by the increasing frequency and severity of climate-related events such as hurricanes, floods, droughts, and heatwaves, alongside longer-term shifts like rising sea levels and higher average temperatures (1). These phenomena are causing significant disruptions to businesses, infrastructure, and communities, leading to substantial economic losses that have the potential to impact financial stability not just of the affected areas but also of the wider economy. At the same time, regulators are intensifying their focus on climate risk management, introducing stress tests, scenario analyses, and mandatory disclosure requirements. Over 50 ministries of finance across the globe have pledged their support for the Helsinki Principles, committing to incorporate climate change considerations into macroeconomic policy, fiscal planning, budgeting, and public investment decisions. Investors and stakeholders are also demanding greater transparency and accountability, integrating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into their decision-making processes (2). Together, these factors underscore why physical climate risk has become a central issue for the financial sector, necessitating proactive strategies to manage and mitigate its impacts.

Data

To date, much of the attention on climate-related financial risks has centred on transitions risks (Carney 2015). In this article, we investigate the impact of acute physical climate risks on the delinquency rates of mortgages in the US and show that, for certain types of these risks, the impacts may be meaningful. The results we present here provide a way for lending institutions to quantify the potential increase in the default behaviour within their portfolios and may be used in calibrations of climate-risk-aware credit risk models, including climate-aware RWA models.

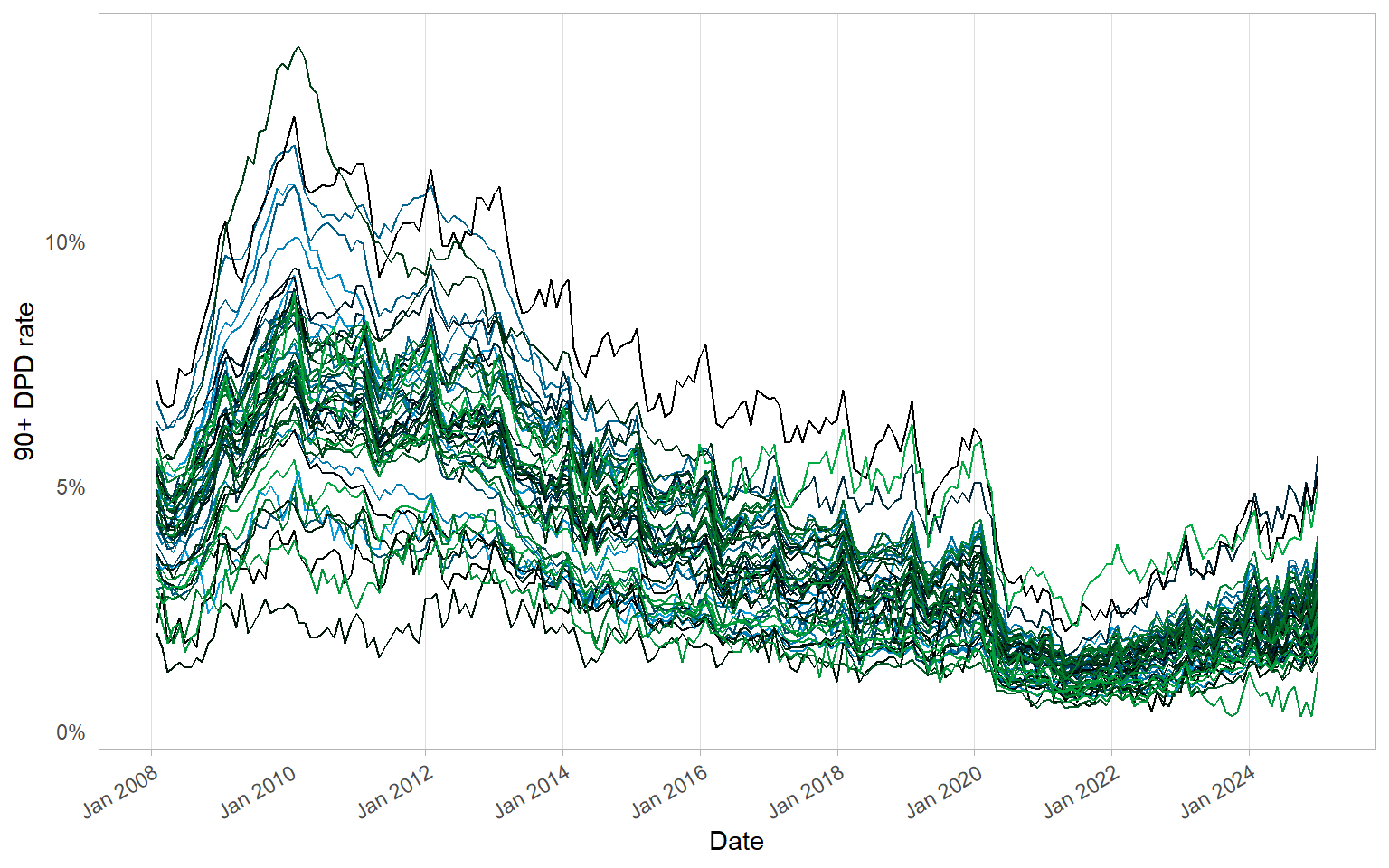

We obtain the data on mortgage delinquency rates (30–90 days past due, 91 and more days past due) from the National Mortgage Database (NMDB), which uses a nationally representative sample of residential mortgages (3). The dataset is at the county-level and covers the period from January 2008 to December 2024. Figure 1 shows the 90+ days past due (DPD) rate in time by US state, aggregated from the county-level data, with significant variations both in time as well as cross-sectionally (4).

Figure 1: The 90+ days past due rates by US state aggregated from the county-level data

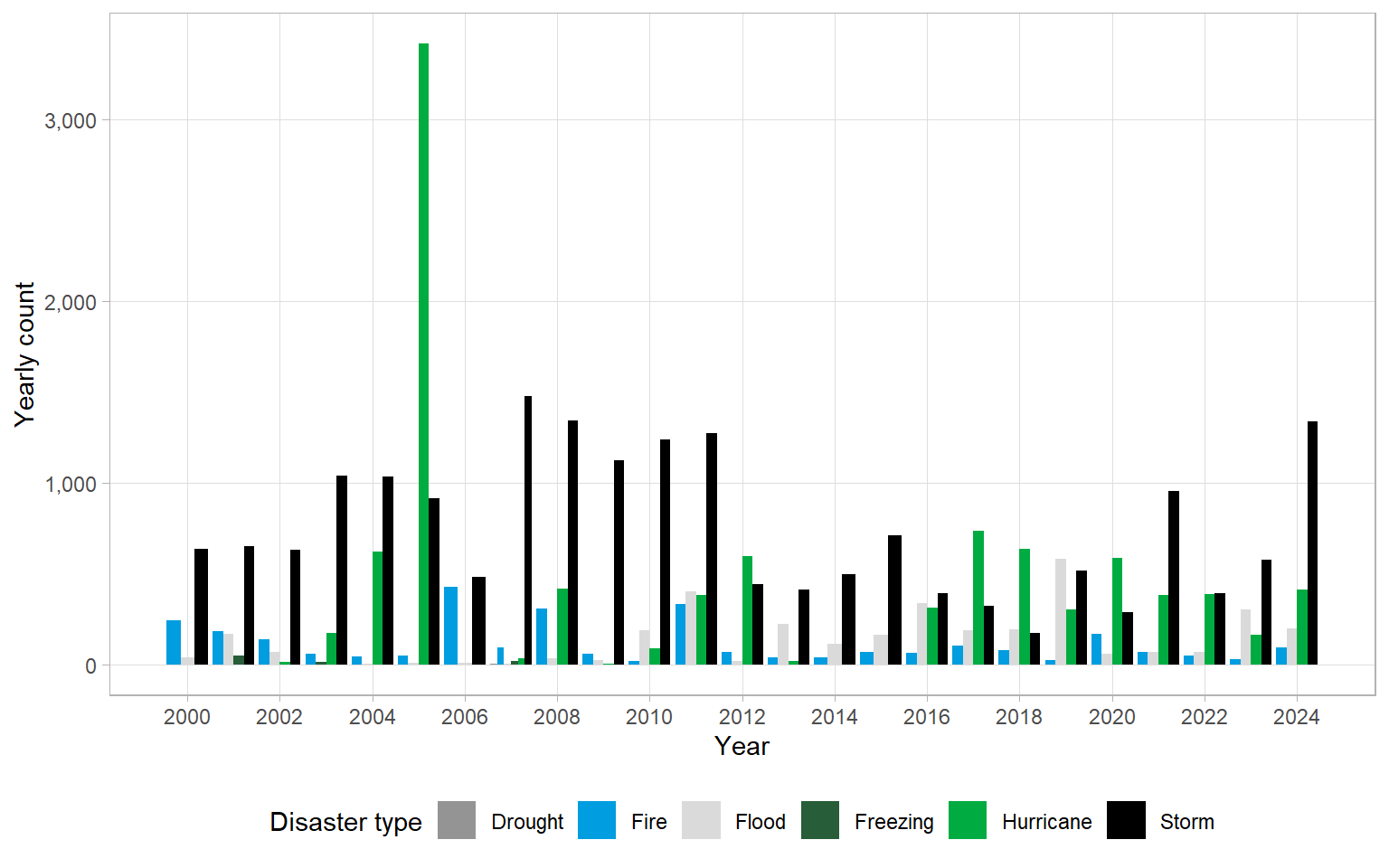

We join this dataset with the Disaster Declarations Summaries data, also at the county-level, maintained by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) that summarises all federally declared disasters (5). Figure 2 shows the number of disaster declarations related to the physical risk types we consider in this article, at the county-level and presented by year. The evident outlier is due to the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season that featured 28 tropical and subtropical storms and, of those, seven were major hurricanes rated Category 3 or higher with four of these rated Category 5.

Figure 2: Number of disaster declarations at the county level by year and disaster type

Results

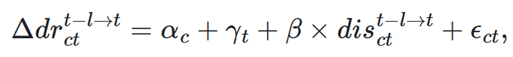

To estimate the impact of the physical risk-related natural disasters shown in Figure 2, we build a panel data fixed-effects econometric model of the form

where

is the difference in the delinquency rate for county

is the difference in the delinquency rate for county  between times

between times  and

and  the county-level fixed effects,

the county-level fixed effects,  the time fixed effects, and

the time fixed effects, and  the number of disasters declared for county

the number of disasters declared for county  between

between  and

and  (6). The results of the estimations are shown in Figure 3 by plotting the impact (in basis points) of a disaster on the delinquency rates across a range of lags. For drought and freezing events, there are not enough unique data points to estimate the model on and, as a result, these two types are not considered further.

(6). The results of the estimations are shown in Figure 3 by plotting the impact (in basis points) of a disaster on the delinquency rates across a range of lags. For drought and freezing events, there are not enough unique data points to estimate the model on and, as a result, these two types are not considered further.

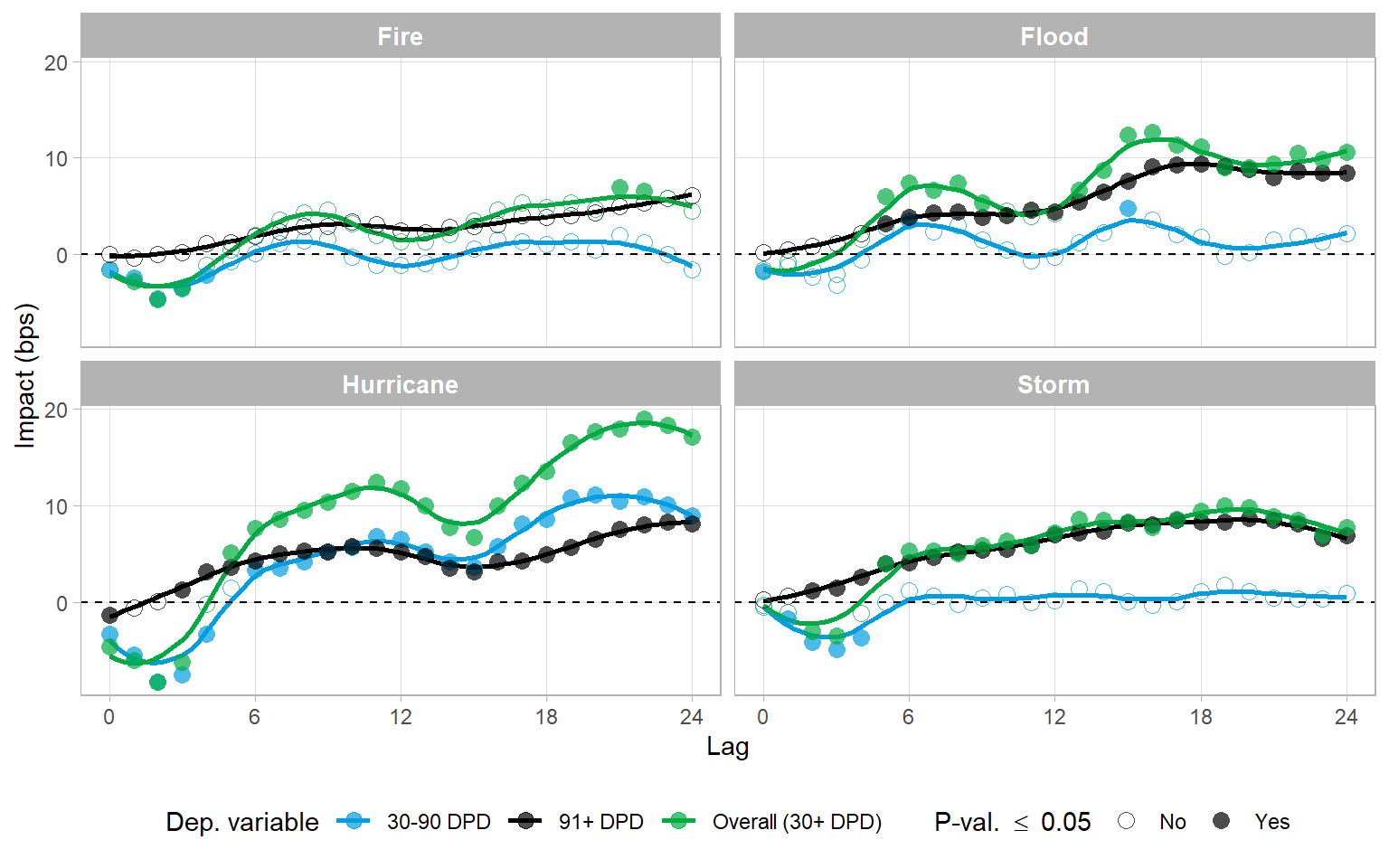

Figure 3: Impact of a single natural disaster on the delinquency rate, by disaster type and lag length

The results reveal a few interesting patterns. First, unsurprisingly, disaster type matters. Fire-related events have very little economic and statistical relationship with the delinquency rates while all other disaster types tend to increase the delinquency rates across a range of horizons in a meaningful manner. Second, this impact tends to be concentrated in the defaulted pool of loans that are more than 90 DPD; apart from hurricanes, these natural disasters do not have a significant impact on the delinquent, but not defaulted, loans that are between 30 and 90 DPD. Third, the impact tends to level off between 18–24 months from when the event occurred with, again, hurricanes being the exception and impacting the delinquency rates in a more persistent manner. Fourth, immediately after the disaster, hurricanes tend to be associated with temporarily suppressed delinquency rates, a result that has been discussed previously by e.g. Gallagher and Hartley (2017) and driven by homeowners using flood insurance to repay their mortgages rather than to rebuild. However, this trend reverses, and after five to six months the delinquency rates increase.

Applications

The econometric model we have estimated equips us with a quantification of the impact of various natural disasters on the county-level delinquency rates. These estimates may be used directly in climate stress tests to understand the potential changes in the credit quality of the portfolio in the face of adverse weather events at the portfolio level or, for example, when calibrating the individual borrowers’ sensitivity to the shocks caused by these disaster types within a Merton model framework (7).

Similarly, this approach may be leveraged by financial institutions that want to understand the impact of acute climate physical risk on their RWAs. While still an emerging field, climate-aware RWA estimation has been gaining traction recently (8), and a framework similar to the one discussed in this article may be employed to quantify the change in the default probabilities of obligors and the resulting capital impact.

References

- Carney, Mark. 2015. “Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon–Climate Change and Financial Stability.” Speech Given at Lloyd’s of London 29: 220–30

- Gallagher, Justin, and Daniel Hartley. 2017. “Household Finance After a Natural Disaster: The Case of Hurricane Katrina.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9 (3): 199–228

- Oliver Wyman, UNEPFI. 2018. “Extending Our Horizons. Assessing Credit Risk and Opportunity in a Changing Climate: Outputs of a Working Group of 16 Banks Piloting the TCFD Recommendations.” UNEPFI Whitepaper

- Pozdyshev, Vasily, Alexey Lobanov, and Kirill Ilinsky. 2025. “Incorporating Physical Climate Risks into Banks’ Credit Risk Models.”

Footnotes

- These two groups of physical risks are typically termed “acute” and “chronic” physical climate risks, respectively

- For more information on the Helsinki Principles, visit The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action at https://www.financeministersforclimate.org/

- The NMDB is a joint project undertaken by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA)

- The apparent seasonality at year-ends is driven by (bad) loan write-offs and subsequent closures typically in January

- We filter this dataset and only consider those disasters that may be classified as manifestations of physical climate risk

- We estimate this model separately for each disaster type and a range of different lags. The reason for differencing the dependent variable is the presence of unit roots in the original time series

- See Oliver Wyman (2018) for an example use of such a model in a climate context

- An example of such a model is that developed by Pozdyshev, Lobanov, and Ilinsky (2025)